‘Myth Buster’ Peter Hein van Mulligen on the Dutch Housing Market

Many Dutch people feel that they are not benefiting from economic progress, inequality is increasing and crime is escalating. Peter Hein van Mulligen, chief economist at Statistics Netherlands, puts an end to these persistent myths. In fact, he says, things have never gone so well. Will it stay that way? What challenges await us? And how do they influence the organisation of the Netherlands?

The Netherlands Are Still a High Trust Society

Van Mulligen’s book Met ons gaat het (nog altijd) goed is an argument for less gloom. We sometimes want to forget that we have made an enormous leap in prosperity in the past century. The average living space per person in the Netherlands has multiplied in a hundred years, we are getting older and we can afford purchases that were out of reach for previous generations. But apparently there is almost nothing that gets used to as quickly as prosperity. Perhaps it is also not sexy to say in a time of global crises, from the corona pandemic to the energy issue, that we are actually doing quite well. “Many Dutch people are convinced that they do not notice economic growth in their wallets and that inequality is growing. Those assumptions are based on emotions, not facts. Inequality, for example, is relatively small in the Netherlands, especially compared to other countries and the Netherlands in the past,” says Van Mulligen. “But there are a number of things that are worrying. These are partly related to the corona pandemic. It seems that this has taken a heavy toll on the mental health of single young people in particular (in 2021, the proportion of Dutch people who are considered to be mentally healthy fell further by 3.2 percentage points to 84.9%, ed.). In addition, the pandemic has shown that there is a significant group of Dutch people who harbor a considerable sense of mistrust towards the government and society. That group continues to stir stubbornly and noisily even after the pandemic. But the vast majority of Dutch people still have a lot of trust in others and in institutions. Despite the fact that trust in politics has peaks and troughs, the Netherlands is in many respects a high trust society. That doesn’t just disappear. Most people are still very committed to others, are members of an association or do voluntary work. So I think the ‘silent majority’, to use a cliché, is still of good will. Unfortunately, we sometimes want to forget that, because the loudest shouters get the most attention. I remain optimistic. We have shown in the past that we can handle many challenges. So we can rely on that a little bit.”

How Housing Determines Our Broad Prosperity

Until a few years ago, prosperity was mainly measured on the basis of economic development. In 2018, CBS started publishing the annual Monitor Brede Welvaart. Broad prosperity encompasses everything that people value: material prosperity, but also matters such as health, education, environment and living environment, social cohesion, personal development and safety. It concerns the quality of life in the here and now, but also how this affects the well-being of people elsewhere and in the future. Housing plays a prominent role in broad prosperity, says Van Mulligen. “The Netherlands are a fairly leveled country, but the place where people live does have an impact on, for example, public health and equality of opportunity for children.”

In the near future, the consequences of climate change threaten to become an additional determining factor in the quality of the living environment and thus our broad prosperity. “The Netherlands is a rich country, but within Europe a country that could be disproportionately affected by climate change. In the most extreme scenario, we gave up the Randstad in 2100 and Amersfoort has become a seaside resort. That possibility is just there. And 2100 is not that far away: many children born now will still be alive. I can imagine that at some point we will see this in the development of housing prices: housing in low-lying areas becomes cheaper, and more expensive in high-lying areas. Energy labels will also be more decisive for the price development of homes,” says Van Mulligen. “Until recently, climate policy was an abstract matter for many people, which did not go beyond the well-known picture of the polar bear on the ice floe. But now that energy prices are skyrocketing, it pays to invest in sustainability measures. Even if you think it’s all nonsense.”

“Young families who can use the large houses of empty nesters are not willing to move to the villages where those houses are located”

Peter Hein van Mulligen

Is There a Trend to Move Out of the City?

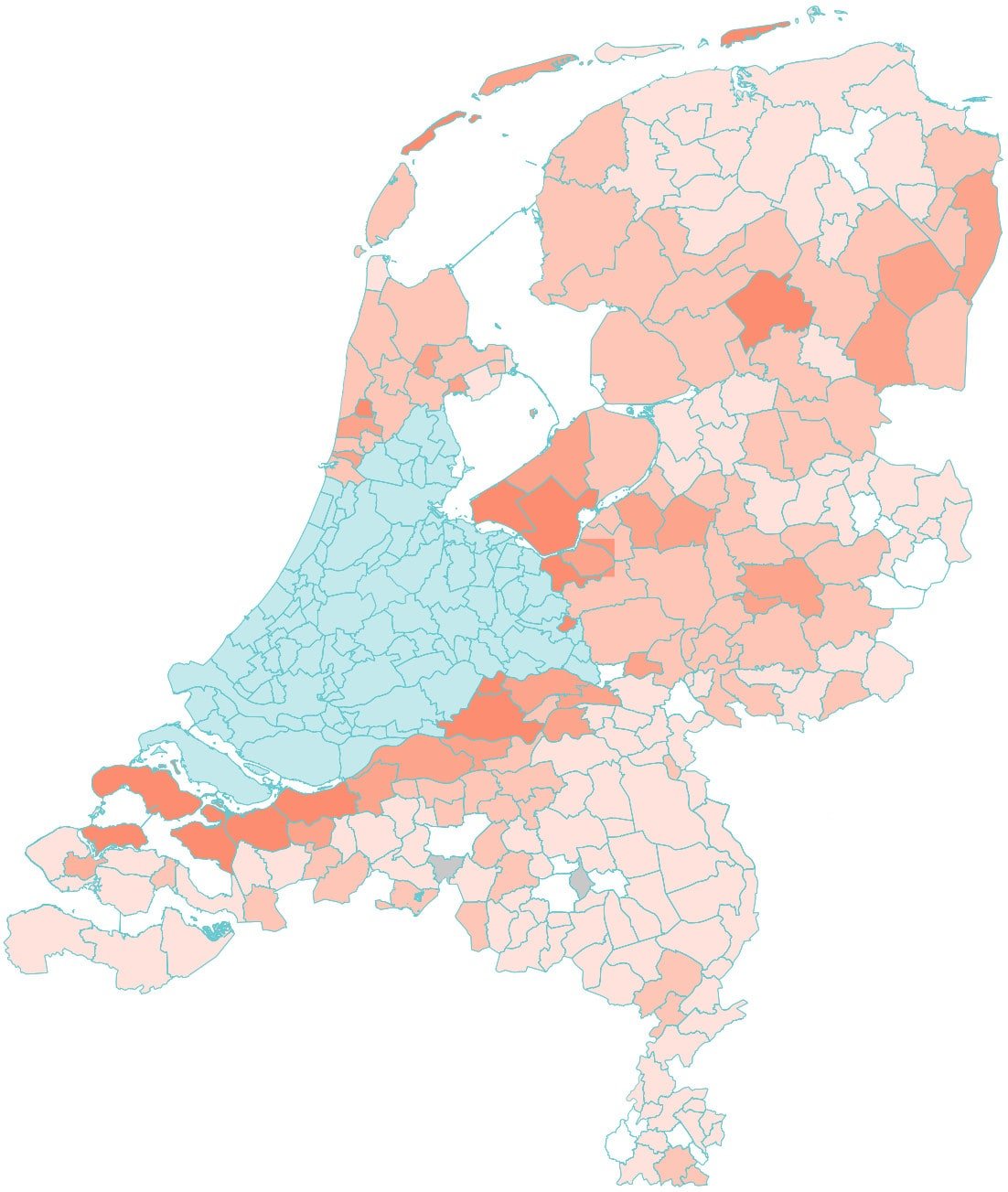

When many employees were forced to work from home during the corona pandemic and foreign migration came to a standstill, life in the city came to be seen in a different light. For a moment it seemed that a serious migration to the countryside was underway. Van Mulligen disputes that idea. “What you still see, even now that the pandemic seems to be behind us, is that most people have a mix of home and office in their working lives. This can be seen, for example, in the occupancy rate of offices on some days. Here at CBS you can shoot a cannon on Fridays. You can also see it in traffic: on Tuesdays and Thursdays the traffic jams are a bit worse than before corona, but on other days they are still much less. And the trains are still a lot emptier. If you look at relocation movements, you see a net migration from the Randstad. The growth within the Randstad is mainly due to migration. But it is not the case that everyone is moving to a hut on the moor: most people are moving to municipalities that are just outside the Randstad. They no longer live in Utrecht or Amersfoort, but in Nijkerk.”

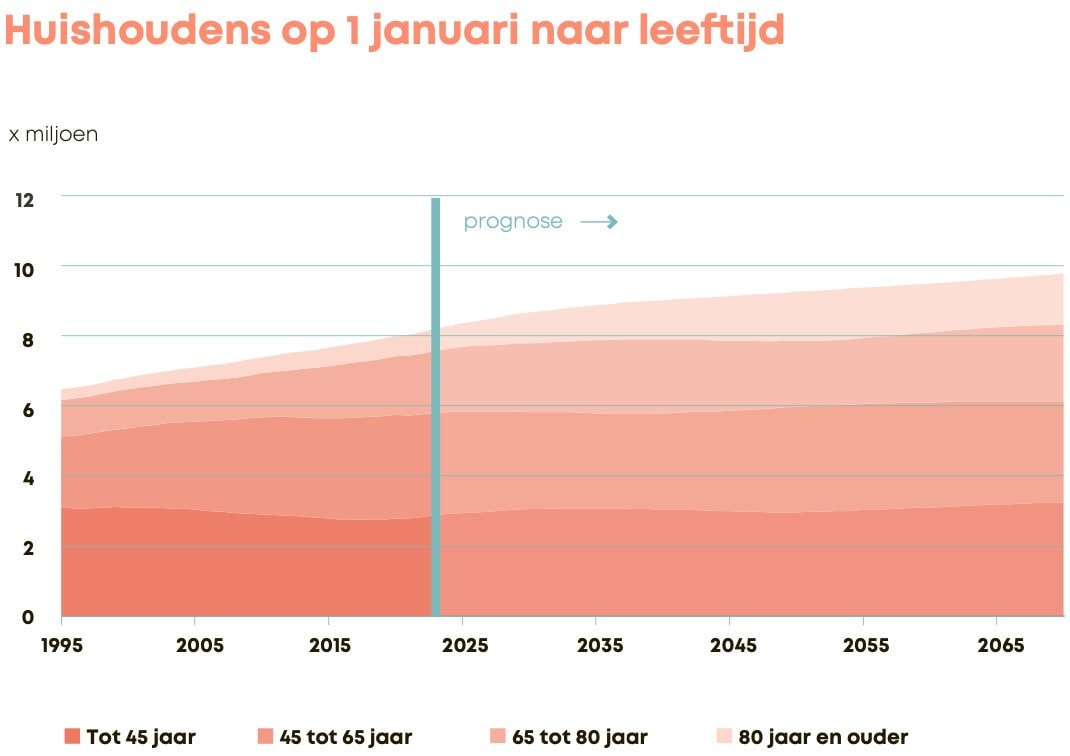

Japan Is Our Foreland

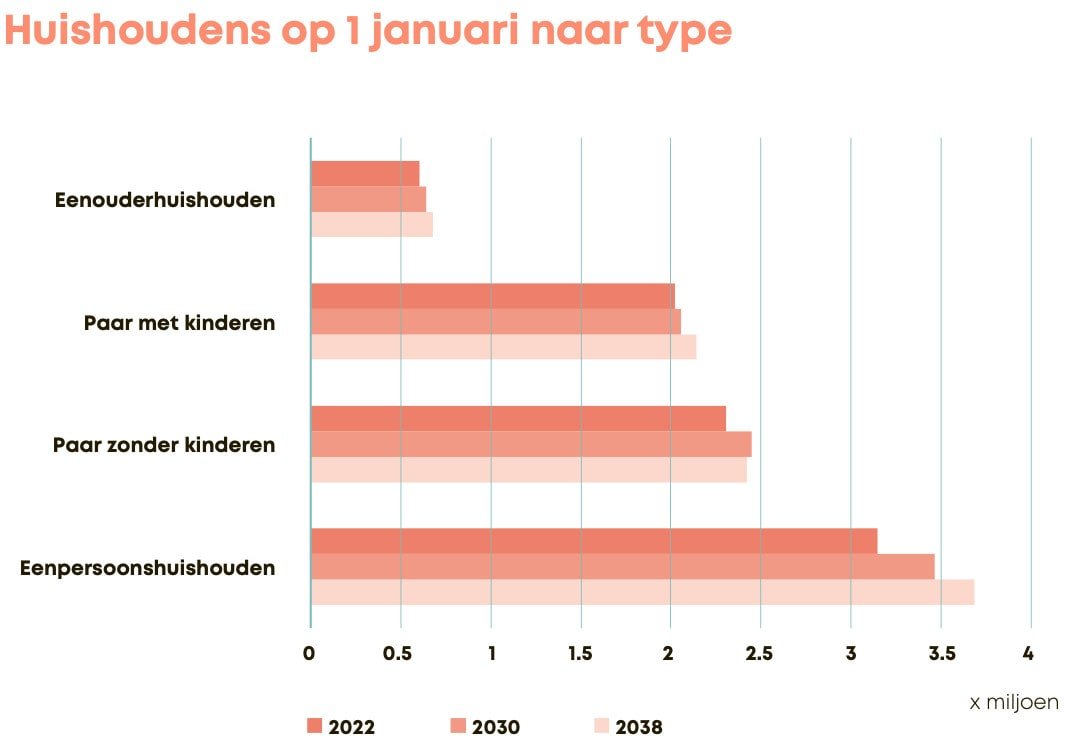

Van Mulligen expects the Dutch population to continue to grow for some time to come. Partly due to the aging population, the number of single-person households and households aged over 75 will increase sharply in the coming years: from 1 to 2 million. “These are not new households, but existing ones. It is not the case that a gray tsunami is coming towards us from Germany.” He believes that too little attention will be paid to the face of the Netherlands when a large part of the population will soon be elderly. “Due to an aging population, our country will undergo drastic economic and social changes. It is an unstoppable process that we are in the middle of. And it never goes away. It is not the case that we are now at a peak and that the proportion of over-75s will fall again in 50 years’ time. It gets high and stays high. The elderly will leave a clear mark on the organization of the Netherlands. And that will lead to many new social discussions about how we want our country to be governed and look like.”

Canceled trains, teacher shortages, long queues at the airport — the shortage on the labor market is taking on serious forms. Van Mulligen has bad news: due to the aging of the population, this problem will only get worse in the coming years. Unfortunately, there are no quick solutions. “The growth in labor supply that we have seen in recent decades is starting to dry up. This was mainly due to the increased labor participation of women in younger age cohorts. At a certain point, these cohorts will reach an age and then the labor supply will no longer increase. Women of 35 now do not work more than women of that age twenty years ago. The structural growth of the labor supply is over, while the aging population continues unabated.” More migration is often wrongly seen as a solution to this problem, says Van Mulligen. “Migration works as a kind of valve for the labor market, which you can use to temporarily relieve the pressure. Migrant workers are getting older, so they will have to be replaced at some point. Another solution is to work more hours or continue to work longer, but those measures are also finite, because there are only 24 hours in a day. That leaves only one option: to increase labor productivity. You do this by working smarter, process innovation and technological solutions. In any case, it remains a complex challenge.” Van Mulligen points to Japan, where robots take over care tasks and construction workers are supported by so-called exoskeletons that ensure that they can do heavy physical work well into old age. “We always thought that aging and all the problems that come with it, such as low inflation and low economic growth, were a typical Japanese problem. But Japan appears to be our foreland.”

Empty Nesters in Big Houses

And then we also have a housing crisis. The government is frantically looking for sites to build 900,000 new homes, while environmental and nitrogen regulations throw a spanner in the works and delay construction processes. A much-heard solution to relieve the pressure on the housing market is to stimulate circulation, especially of empty nesters who live in large houses. But is it really that simple? “Many elderly people continue to live in the same house, even once the children have left home. Then you may wonder why those people, especially if the partner has died, want to continue living in a house with four bedrooms. Don’t they have other needs? This is partly the case: many over-75s would like to move on to a more suitable home, such as sheltered housing and senior courtyards where they can continue to live on their own until later in life. But the question is whether young families who can use the large houses of empty nesters are willing to move to the villages where many of those houses are located. The areas where the concentration of over-75s is rising the most are not the areas with the greatest shortages on the housing market.” In short, the geographical component is too often ignored, says Van Mulligen. If a major house exchange were to take place, many people might end up in the desired type of home, but not in the desired location. “Unfortunately, you cannot just pick up a house in Delfzijl and place it in Rijswijk or Amstelveen.”

“The share of single-family homes in the Netherlands is very high compared to other European countries. We have a blind spot for living in apartments“

Peter Hein van Mulligen

Up, Up!

Van Mulligen states that there is a great need for single-family homes in or close to the Randstad conurbation, where the battle for space is already fierce. In order to increase the supply in desirable places, we may sometimes say goodbye to entrenched ideas about living. “When we think of a house for a family with two children, we automatically think of a house with a garden and a parking space in front of the door. That’s a very Dutch thing. Many newly built single-family homes could also be apartments. We have a bit of a blind spot for that. The share of single-family homes here is very high compared to other European countries. That is extra strange when you consider how small and densely populated the Netherlands is. For example, the population density in inhabited areas in Sweden is much higher than here, simply because there are many more Swedish households living in apartments. These can be spacious homes of 150 square meters, with enough bedrooms for an entire family.” Eventually we will have to, thinks Van Mulligen, whether we like it or not. “If you read those stories about lack of space, about increasing noise nuisance in residential areas, because people are building in places where noise standards are exceeded… we cannot avoid building more in areas that are already urban. That means that we have to take to the air and not designate a new polder again and again where all single-family homes are being built. By the way, they are not that unhappy in Sweden.”