A Stroll Around Hong Kong With Michael Leung

Originally from London and now based in Hong Kong, Michael Leung is an artist, educator, urban bee-carer and everything in between. While being a designer and lecturer, he also channels his energy into building community resilience by engaging and supporting local food and production. In Michael's interview, we get a glimpse of his everyday life, the evolving social relations under the pandemic, and the possibilities that emerge from being engaged in the micropolitics of the city.

I first moved to Hong Kong in 2009 to do a masters course at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Before then, I was designing mobile phones in London. I came here because I am familiar with this place from when I was younger and visited during school holidays. My grandma is also here and she’s very old. The masters was only for one year, and I didn’t know how long I would be here for, but straight after I graduated, I asked if I could teach at the university and they accepted — I taught there for five years. In a way I kind of just stayed with this pattern of teaching in September until June and then having my own time to work on my projects.

From ‘Activists’ to ‘Active Citizens’

Pankerchief is a project, but it’s also about advocating with the fabric sellers — it’s part of a social movement and is a form of resistance. These small supportive gestures within social movements are important activities. I don’t plan to leave Hong Kong because I’m still doing my PhD and there are some issues that are unresolved — some might say these issues may never be resolved because it’s an unfair government. I understand that the political situation is really tough but I want to bear witness to it and see if I can support in any way.

I’m uncomfortable with the title ‘activist’ because I think having certain names, roles, or professions really fixes you. People can be pigeonholed and I prefer to be more flexible and fluid. When I was in India, I went to Aarey forest in Mumbai, where I met someone called Amrita who’s been working against the deforestation and metro development plan. She called herself an ‘active citizen’ which is a really nice term because it shows that anyone can be active and have agency.

Evolving Neighbourhood Relations throughout the Pandemic

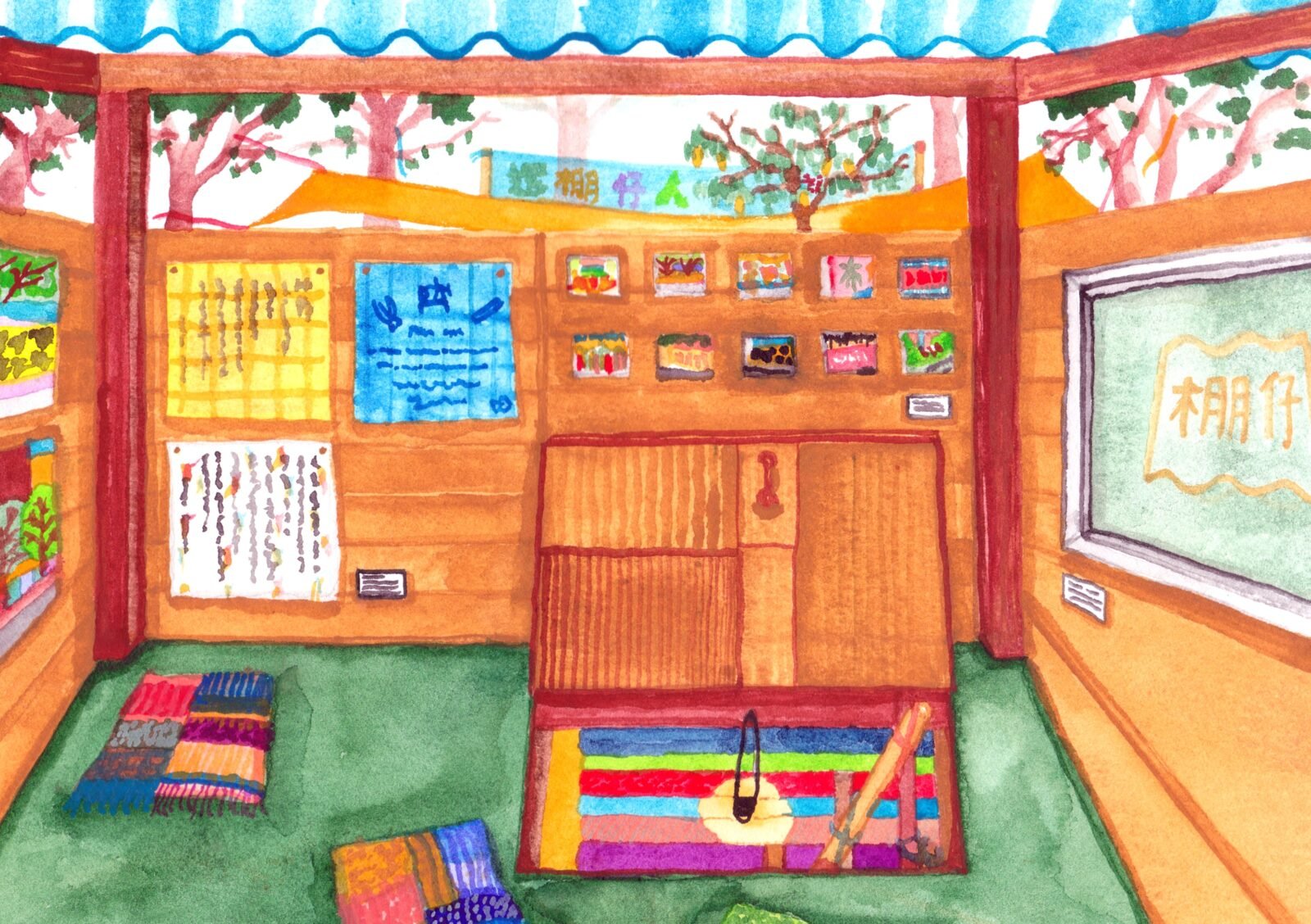

When I think of the pandemic and this neighbourhood, I think about our market stall Kai Fong Pai Dong, and how we haven’t been open for a very long time. Primarily because of the social movement and now with the pandemic it’s become even more difficult. But also because during the pandemic there are other issues happening such as the village evictions in places outside the city, which is really horrible. I guess in relation to this neighbourhood, I found myself, when speaking to the members of the community, more focusing on the urgent and unstable places rather than the social movement.

Yesterday when I was composting I brought the box of organic waste to show it to the owner of a hardware shop — she has access to some land for farming and it’s quite cheap, only 12,000 HKD per year. Some neighborhood relations have still been nurtured or continued — like the market where I buy my vegetables or my tofu from. Since I’ve been going to farming villages, I’ve been getting a lot of produce like fruits and vegetables — so I give some to the owner of a Nepalese shop. Sometimes she gives me a samosa or some Nepalese snacks in return. This gift economy has been established with her during the pandemic.

Building Resistance by Connecting People to Food

I just finished teaching for 13 weeks and the class was on a Monday morning. Every Sunday I would go to Mapopo to buy vegetables, fruits and banana bread. So for most of the classes or at least half of them, I would bring locally grown bananas or banana bread made by my friend to class. I would share them with the students because I don’t see them at these farms. For any land resistance movements, I think it’s essential to connect people back to the food that they eat.

In the past, I’ve also done village tours to students and my research group. I think this is really important because some people might want to go but they just don’t know how to get there or have concerns about walking in villages by themselves. I think spending time sharing these places with people before they disappear is really meaningful.

Making Hong Kong a Better Home for Everyone: Engaging in the Micropolitics of the City

Recently I’ve been visiting detainees at the immigration center in Hong Kong. I’ve been thinking a lot about my experience in France this year when I went to the autonomous territory where some refugees live. We were learning French together in some French classes.

I started to think about that experience in relation to the detainees in Hong Kong who are from Africa, Pakistan, South America, Indonesia, etc. and how in Hong Kong, the government makes it illegal for refugees to work or do volunteer work. In other words, it forces refugees to look for different ways of survival which the government will say is illegal. One refugee used to be a farmer in his country. I’ve been trying to connect with him to see if he’s interested in visiting some farms in Hong Kong. I’ve been thinking of this idea of later renting a farm or a piece of land and potentially having it as a place that is open to everyone to grow their own food as another way of survival.

It’s a really politically disturbing time in Hong Kong now with the national security law. Many people have left Hong Kong. In the past year, we’ve seen protest days where 2 million people were walking on the streets. I hope that some of those people could focus on the micro-politics of the city — such as those in the villages or immigration centre. To support those communities and work together in achieving some sort of fair, just and equitable solution or outcome. My aspirations are that through teaching or sharing research, I can contribute in some way to keep people engaged and allow the city to be a better home for everyone. This is definitely not just a local effort, similar things are happening globally — if we can connect with other social movements and learn from each other, we will all be in a much stronger and better position.