This British Architect Heralds a New Era of Urban Social Housing

Just as the housing market in many capital cities is becoming more and more investment-oriented and affordable only for the wealthy, British architect Peter Barber is taking a stand for social housing. Over the past years, his office has delivered a number of innovative projects catering to those in need of affordable housing — or even housing at all.

Working predominantly in London, the firm proposes schemes that are a far cry from what is common in social housing. Barber’s designs are characterized by a reworking of traditional British housing typologies and a clean aesthetic. While still in harmony with its surroundings, every project emanates a distinct identity. His approach reminds of Cornelis van Eesteren’s three hallmark principles of light, air and space and at the same time he’s considered a master of humane high-density. And most importantly, Barber’s architecture is informed by a sense of humanity and neighborliness. “The focus of all of these projects is the design of a public or shared space that brings people into close proximity, making them highly visible to one another and therefore more likely to actually meet,” Barber stated in an essay for the Architecture Foundation about his work.

For example, the East London neighborhood of Barking recently saw the completion of two rows of single-story homes for people over 60. Inspired by South London’s Choumert Square, the rows are facing each other, providing residents with a small front yard to be personalized with greenery and outdoor furniture as they please. Ultimately, the aim is to get people out into their front yards and socializing with neighbors — an attempt to stimulate and foster companionship in a time of growing loneliness among the elderly.

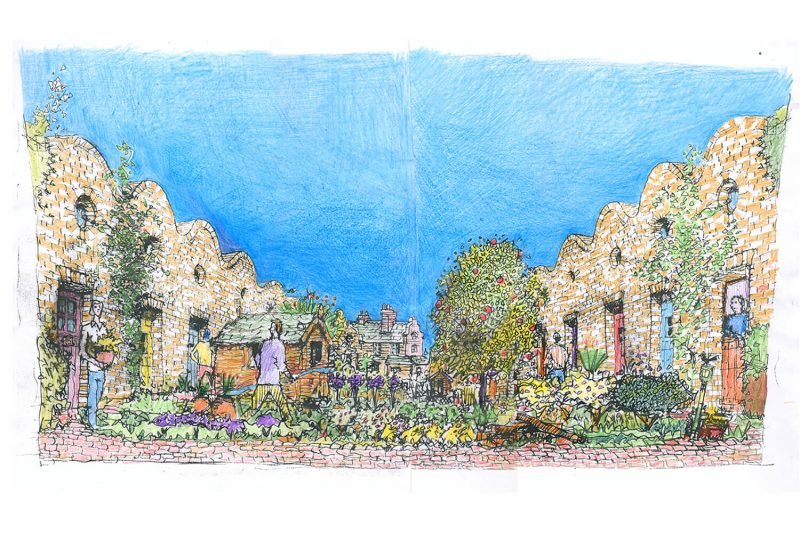

Another applauded project of the past year has been the courtyard formation of towered houses at McGrath Road in East London, representing a radical reworking of the Victorian low-cost, high-density typology of back-to-back housing that was common at the time. The result is what The Guardian called “a chunky, microcosmic citadel of three- and four-storey town houses, each with their own front door.” In line with the bungalows for seniors mentioned earlier, Barber is counting on the agency of residents to actually activate the square by populating it with planters, furniture or whatever else will make it a lively space.

Barber has also designed for those who don’t have a permanent place to stay for themselves. Mount Pleasant is a sheltered housing project for homeless people, centered around a tree-lined courtyard with shared facilities and spaces to sit, offering a place to stay for both those who are relatively independent and those who struggle to get about. Unplanned encounters between staff and residents are a vital means of engagement and care for residents, says the studio. And at Holmes Road, the architect tried to create a homely, domestic atmosphere by including a number of little studio houses with a small bathroom and mezzanine bed space facing a courtyard with a communal garden. These features offer residents a sense of perspective.

Where innovative projects such as the 3D-printed social housing in Nantes and shipping containers-turned-microhomes in Germany are more research-based ‘solutions’ in the face of the social housing crisis, the approach taken by Barber’s team (as well as the local councils that commission them) and initiatives such as the London Community Land Trust — which works with teams of local residents to create truly and permanently affordable homes that are owned and run by local people — is more community-centered. Countering our recent coverage of the growing trend of urbanites around the world moving out to small and mid-sized cities, then, the designs of Peter Barber Architects provide inspiring examples of how to organize affordable and humane housing within city limits.