The Ideal City: A Manifesto of Hope for the Urban Future

The book The Ideal City takes us on a journey of human creativity. Various examples from around the world paint a picture of the optimistic city of the future and how to get there.

The authors do not provide a formula for an ideal city. Instead, they present a collection of human ingenuity, expressed in various projects in the fields of city planning, architecture, design and community governance. All these projects share a contagious idealism. We see an ideal city that is imaginative, accessible, shared, safe and desirable, illustrated by examples from 60 cities in 30 countries.

The Resourceful City

The first chapter is about inventive cities that are sustainable in terms of the materials used, energy consumption, water management and food production. The chapter includes a profile of Canadian architect Michael Green, who advocates the use of wood as a building material as an alternative to steel, which is responsible for 11% of global greenhouse gas emissions. With all the awareness that forestry is a harmful industry, Green sees a future in the use of wood, even in large-scale projects, and emphasises the importance of looking at the whole life cycle of the material. Climate Tiles are an interesting example of creating simple but innovative solutions. The tiles covering a stretch of pavement in Copenhagen contain a system of holes and channels to distribute rainwater. Instead of channelling the rainwater into the sewers and putting a burden on them, it is distributed to the green areas around the pavement.

The Accessible City

The second chapter is a story of an accessible city that values diversity, inclusion and equality. Accessibility here is understood as fair access to the housing market, inclusive governance and sensitivity to the needs of different social groups, such as people with physical disabilities. Urban-Think Tank — an interdisciplinary group of architects, civil engineers, environmental planners, landscape architects and communication specialists who combine research with design in their work — will be featured. Areas of informal settlement, such as in Venezuela, are a focal point of their work. Two projects in Caracas are examples of solutions that have emerged from carefully listening to the needs of the residents and observing the local built environment. (For an in-depth look at U-TT’s work in Caracas, the book Torre David: Informal Vertical Communities is highly recommended.)

The Shared City

The third chapter deals with the theme of sharing. This applies to the sharing of housing, the workplace, transport and various services. Sharing can be an answer to both environmental and social problems, such as the need to reduce consumption, improve mobility or tackle loneliness. The chapter looks at several shared living initiatives, including a house for female residents in North London that combats ageism and provides a place where older women can maintain their independence and sense of empowerment. The residents contribute to the maintenance of the house and garden and participate in communal activities. Another co-housing project is an intergenerational house in Amsterdam, which provides economic and social benefits to the family while allowing members to maintain a degree of autonomy. A similar project from Seattle, on the other hand, brings together a diverse group of residents and provides housing with flats of different sizes and shared spaces, including a rooftop vegetable garden. Much larger community gardens can also be found on the other side of the United States. In the North End district of Detroit, as in many other places in America, residents have problems accessing nutritious food. The Michigan Urban Farming Initiative is one of the answers to tackle this problem. The community garden is managed by an NGO and relies on the work of volunteers. The garden delivers its produce free of charge to 2,000 households in the area.

The Safe City

The third characteristic of an ideal city is security. And the authors of the book do not see this merely as preventing and combating crime on the streets. A safe city is one that protects its inhabitants from extreme weather conditions, provides access to clean resources such as water and air, and cares for people’s mental well-being. A Scandinavian project shows how prison design can support the rehabilitation process of prisoners. In the Norwegian prison, large vertical bulletproof windows replace bars and allow inmates to interact with the surrounding greenery; a shared kitchen and living room allow for safe interactions with others; and a wide range of sports and educational facilities offer hope for behavioural change, all leading to lower recidivism rates. Another initiative deals with safety in a more direct sense. Kwanlin Dün First Nation Community Safety Officer is a unit that operates in Whitehorse, a small city in northern Canada, and looks after the day-to-day safety of the urban First Nations community. The officers are members of the community themselves, which is important given Canada’s colonial roots. They do not carry weapons and their work is based on preventive action. They are trained to deal with people suffering from addictions, mental crises or trauma, know how to de-escalate tense situations and have knowledge of family dynamics and adolescent behaviour. Sometimes they just take care of the community as neighbours, take elderly people to the doctor or do the shopping.

The Desirable City

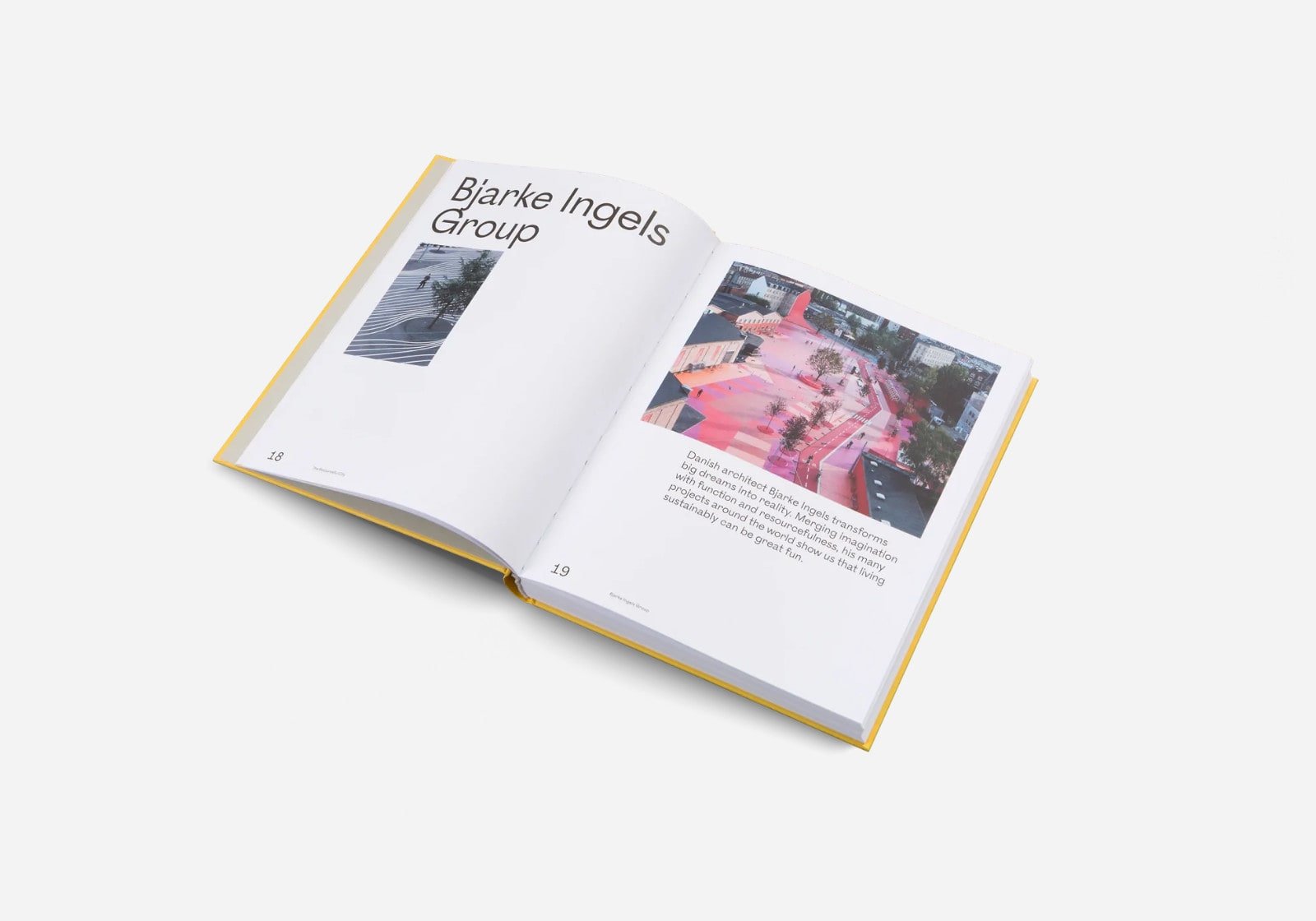

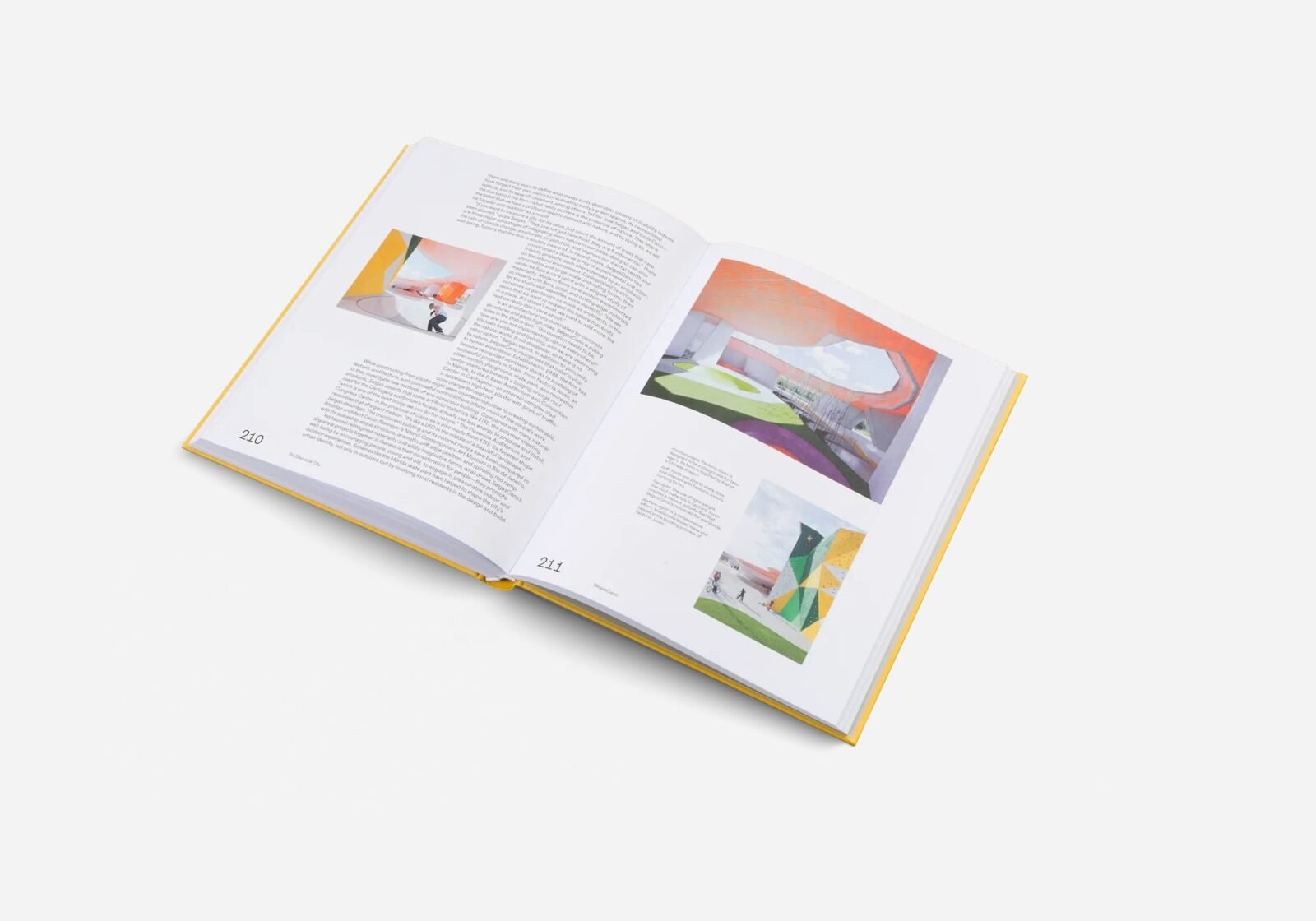

The final chapter is a paean to fun. For a city should not only be resilient, well planned and well connected, but also simply cool. A desirable city is one that excites and amazes the senses. It is a place built on a human scale, with lively streets and eye-catching architecture. This chapter should not forget the work of Danish urban planner Jan Gehl, who devoted his life to researching and intervening in urban spaces to encourage people to go out into the streets, be with other city dwellers, look at them and even interact with them. SelgasCano, on the other hand, is a beneficial sensory experience. The wealth of colours and shapes in the architecture of this Madrid-based firm, despite its contrasting nature, maintains a close contact with the surrounding nature. A cool city implies interventions on different scales. It may be the transformation of a busy road intersection into a pleasant square, as in the Spanish city of Òdena, or the creation of a permanent daily market, much needed for the economic development of the area around the city of Dandaji in Niger, where simple and ingenious metal disc parasols resembling tree crowns protect users from the burning sun. But it can also be something small, like painting a subway in bright colours to neutralise the unpleasant feeling of walking through such spaces, or installing playful urban furniture to add variety to simple sitting.

The Ideal City goes beyond the usual image of skyscrapers drowning in greenery and surrounded by self-driving cars. It offers us a place that is not a paradise, terrifying in its perfection and accessible only to a select few, but a place that we may have seen before and is therefore more real and simply more human. We need positive visions for the future and not just one, but many different ones. This clearly structured and tastefully illustrated book is a great addition to the library of any pragmatic urban idealist. What does your ideal city look like?

Information

The Ideal City: Exploring Urban Futures

Editors: Gestalten and SPACE10

Publisher: Gestalten

Publishing date: April 2021

Language: English

Full colour, hardcover, stitch bound, 256 pages

ISBN: 978-3899558623